About

Type: Extant

Parish: St.John

Founding date: 1671

See on Google Maps!

Current Status

The large Wood plantation estate house built approximately 200 years ago, is still in its original condition and is the home of Phillip and June Abbott, heirs of Nellie Abbott. They continue to run a working farm and a small store selling feed and other livestock needs to farmers and homeowners.

Phillip and June are proud owners of one of the few remaining estate houses left in Antigua. They own an abundant collection of old maps, photographs, furniture, and other mementos of their ties to their historical heritage. Philip is an avid researcher of genealogy, and can provide a detailed history of the Abbott, Sutherland, Goodwin, and Maginley families to whom he is related. He also has considerable information on other families he has encountered in his research. The Abbott family immigrated to Antigua in the early 1800s from County Leitrim, Ireland.

The house design is typical of many of the old estate homes, with steps leading up to a veranda on the second story, which opened into the living and dining rooms. Bedrooms were located on either side, each with a dressing room later converted into bathrooms. A kitchen was added upstairs to the rear of the dining room. It had previously been located in the backyard, separate from the main house, because of the danger of fire. When it was customary to cook with wood or charcoal.

The second story of this home is constructed of wood set on a first story of stone, which contained the store rooms. This construction permitted the second-story living space to be cooled by trade winds, while the thick stone walls below helped maintain a cooler temperature.

The manager’s house, which no longer exists, was south of the buff house on a small rise. Neither the sugar mill itself nor the extensive works exist today, but some of the outbuildings, old cisterns, and ponds can still be noted.

Estate Related History/Timeline

House of Lords, 20th March, 1671: “Holdsworth vs. Lady Honywood. Petition of Wm. Holds worth, son-in-law, and administrator (with the will annexed) of the goods and estate of John Wood, complaining of a discussion of his Bill in Chancery in 1646 concerning some estates of John Lamont.“ Parliamentary Archives, Ref. HL/PO/JO.

In 1958/59, the “buff” was rented by a young U.S. Navy Lieutenant and his wife, Woody and Anne Barnes. There was no housing on the Navy Base at the time, and they thought it romantic to be living in an old plantation house. The cane fields almost abutted the house, and Woody recalls an afternoon when a cane field caught fire, causing considerable anxiety about the safety of the home. Several people arrived and assisted the fire department in cutting a cane break to contain the fire. Woody and Anne also benefited from the friendship of old Fred Abbott, Phillip Abbott’s father, who lived next door in the manager’s house and who acquainted them with some of Antigua’s history.

In 1779, when the estate was owned by Jonas Langford Brooke, there is a document reference to “Langford’s Body Plantation in St. John’s”, hence the alternate name (rarely used) for this estate. By 1816, it was clearly identified as “The Wood estate in St. John’s division containing 325 acres,” according to Vere Oliver’s Volume II. He cites a second reference which clarifies that the estate had two names: “The Body or Wood Estate . . . containing 28 acres, 3 roods,” which was “indentured on 19 April 1816 between Thomas Langford and Johnathon Dennet for one year.”

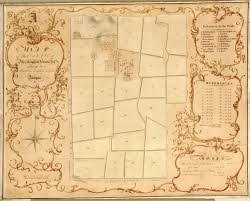

By 1825, there were three estates owned by Peter Langford Brooke, an obvious relative of the Langford family (see Langford’s #6). According to Phillip Abbott, documents show “P. L. Brooke was the owner from 1829 and then his heirs to 1878. He died in England in 1840 by drowning while skating on a frozen lake, and the ice broke. The three estates were Langford’s (#6), The Wood (#12), and Jonas (#85). I (Phillip Abbott) now lived at The Wood. The house is about 200 years old, and I was lucky enough to acquire a plan of the house and estate drawn by Peter Langford Brooke in about 1825. There are also plans for Langford and Jonas. #4 – Hodge’s (Bay) Plantation

“PETITION. A Petition of Mary Prince or James, commonly called Molly Wood, was presented, and read, setting forth, That the Petitioner was born a slave in the colony of Bermuda, and is now about forty years of age; That the Petitioner was sold some years ago for the sum of 300 dollars to Mr. John Wood, by whom the Petitioner was carried to Antigua, where she has since, until lately resided as a domestic slave on his establishment; that in December 1826, the Petitioner who is connected with the Moravian Congregation, was married in a Morovian Chapel at Spring Gardens, in the parish of St. John’s, by the Morovian minister, Mr. Ellesen, to a free Black of the name Daniel James, who is a carpenter at Saint John’s, in Antigua, and also a member of the same congregation; that the Petitioner and the said Daniel James have lived together ever since as man and wife; that about ten months ago the Petitioner arrived in London, with her master and mistress, in the capacity of nurse to their child; that the Petitioner’s master has offered to send her back in his brig to the West Indies, to work in the yard; that the Petitioner expressed her desire to return to the West Indies, but not as a slave, and has entreated her master to sell her, her freedom on account of her services as a nurse to his child, but he has refused, and still does refuse; further stating the particulars of her case; and praying the House to take the same into their consideration and to grant such relief as to them may, under the circumstances appear right. Ordered that the said Petition do lie upon the table.”

In the following text, Mary (aka Molly Wood) describes her life as a slave in the Wood household, as excerpted from The History of Mary Prince (author unknown):

“Mr. Wood took me with him to Antigua, to the town of St. John’s, where he lived. This was about fifteen years ago. He did not then know whether I was to be sold; but Mrs. Wood found that I could work, and she wanted to buy me. Her husband then wrote to my master to inquire whether I was to be sold? Mr. D____ wrote in reply, ‘that I should not be sold to anyone that would treat me ill.’ It was strange he should say this, when he had treated me so ill himself. So I was purchased by Mr. Wood for 300 dollars, *(or £100 Bermuda currency).

“My work there was to attend the chambers and nurse the child and to go down to the pond and wash clothes. But I soon fell ill of the rheumatism and grew so very lame that I was forced to walk with a stick. I got the Saint Anthony’s fire, also, in my left leg, and became quite cripple.

No one cared much to come near me, and I was ill a long, long time; for several months, I could not lift the limb. I had to lie in a little old out-house that was swarming with bugs and other vermin, which tormented me greatly, but I had no other place to lie in. I got rheumatism by catching cold on the pond side, from washing in the freshwater; in the salt water I never got cold. The person who lived in next yard (a Mrs. Greene) could not bear to hear my cries and groans. She was kind, and used to send an old slave woman to help me, who sometimes brought me a little soup. When the doctor found I was so ill, he said I must be put into a bath of hot water. The old slave girl got the bark of some bush that was good for the pains, which she boiled in the hot water, and every night she came and put me into the bath, and did what she could for me: I don’t know what I should have done, or what would have become of me, had it not been for her — My mistress, it is true, did send me a little food; but no one from our family came near me but the cook, who used to shove my food in at the door, and say; ‘Molly, Molly, there’s your dinner.’ My Mistress did not care to take any trouble about me; and if The Lord had not put it into the hearts of the neighbors to be kind to me, I must, I really think, have lain and died.

“It was a long time before I got well enough to work in the house. Mrs. Wood, in the meanwhile, hired a mulatto woman to nurse the child; but she was such a fine lady she wanted to be mistress over me. I thought it very hard for a coloured woman to have a rule over me because I was a slave and she was free. Her name was Martha Wilcox; she was a saucy woman, very saucy; and she went and complained of me, without cause, to my mistress, and made her angry with me. Mrs. Wood told me that if I did not mind what I was about, she would get my master to strip me and give me fifty lashes; ‘You have been used to the whip,’ she said, ‘and you shall have it here.’ This was the first time she had threatened to have me flogged; and she gave me the threatening so strong of what she would have done to me, that I thought I should have fallen down at her feet, I was so vexed and hurt by her words. The mulatto woman was rejoiced to have power to keep me down. She was constantly making mischief; there was no living for the slaves — no peace after she came.

“I was also sent by Mrs. Wood to be put in the Cage one night, and was next morning flogged by the magistrate’s order, at her desire, and this all for a quarrel I had about a pig with another slave woman. I was flogged on my masked back on this occasion; although I was in no fault after all; for

old Justice Dyett, when we came before him, said that I was in the right, and ordered the pig to be given to me. This was about two or three years after I came to Antigua.”

In the same book, John A. Wood is quoted in an August 18, 1828 court document as follows:

“The paper which Mr. Wood had given her (Molly) before she left his house, was placed by her in Mr. Stephen’s hands. It was expressed in the following terms:–

“I have already told Molly, and now give it her in writing, in order that there may be no misunderstanding on her part, that as I brought her from Antigua at her request and entreaty, and that she is consequently now free, she is of course at liberty to take her baggage and go where she pleases. And, in consequence of her late conduct, she must do one of two things — either quit the house, or return to Antigua by the earliest opportunity, as she does not evince a disposition to make herself useful. As she is a stranger in London, I do not wish to turn her out, or would do so, as two female servants are sufficient for my establishment. If after this she does remain, it will be only during her good behavior; but on no condition will I sallow her wages or any other remuneration for her services. /s/ John A. Wood, London, August 18, 1828.”

In 1833, following the British Parliament’s ruling abolishing slavery in the British Empire, the Crown made a legacy award (Antigua 105) to Peter Langford Brook of £2,461. 7s. 7p. for granting freedom to 190 enslaved workers on the plantation.

By 1852, Thomas Langford Brook owned Langford’s (#6) 404 acres and The Wood’s (#12) 280 acres, both in St. John’s Parish, as well as Jonas’s (#85) 325 acres in St. Peter’s Parish, and Laroche’s (#135) 231 acres in St. Paul’s Parish. Ten years earlier, two other estates were sold, the whole of the Antigua property, totaling about 1,700 acres, for £10,000 to Aubrey J. Camacho. As noted in previous estate descriptions, by 1891 Mr. Camacho owned eight plantation estates, including Bellevue (#36), Briggin’s (#22), Langford’s (#6), Mount Pleasant (#7), Dunbar’s (#8), Otto’s

(#16), The Wood (#12) and Jonas’s (#85). All but the last were located in St. John’s Parish.

Helen (Nellie) Abbott, who is part owner of The Wood as of 1985, remembers her grandmother Millicent Sutherland, who owned it in 1938 and had grown up there with her siblings:

“Granny Sutherland always kept cows and sold milk. She also worked at the Sugar Factory weighing cane for the Syndicate Estates and would walk from The Wood to the “Factory through the back roads. Millicent Sutherland rented the land at The Wood in one acre lots (grounds) or more to peasants who grew cotton, sugar cane or vegetables. Where the Epicurean now stands there was a large field of tomatoes. I used tohelp our maid, who had a ground, pick cotton, and she would roast sweet potatoes in the ground to feed us.”

In 1941, the Antigua Sugar Factory Ltd. had cane returns of 1,060 tons. The 106 acre estate was worked by peasants who delivered 752 tons of sugarcane to the factory.

The Woods Mall was constructed on The Wood estate land, hence the retention of the name.

Enslaved People’s History

Based on contemporary research, we have little information to share about the enslaved peoples from this plantation at this time. However, we will continue our quest for more information about these vital individuals. There were at most 190 slaves. In 1833, following the British Parliament’s ruling abolishing slavery in the British Empire, the Crown made a legacy award (Antigua 105) to Peter Langford Brook of £2,461. 7s. 7p. for granting freedom to 190 enslaved workers on the plantation. Phillip Abbott writes about Molly Woods, a slave, and states, “”PETITION. A Petition of Mary Prince or James, commonly called Molly Wood, was presented, and read, setting forth, That the Petitioner was born a slave in the colony of Bermuda, and is now about forty years of age; That the Petitioner was sold some years ago for the sum of 300 dollars to Mr. John Wood, by whom the Petitioner was carried to Antigua, where she has since, until lately resided as a domestic slave on his establishment; that in December 1826, the Petitioner who is connected with the Moravian Congregation, was married in a Morovian Chapel at Spring Gardens, in the parish of St. John’s, by the Morovian minister, Mr. Ellesen, to a free Black of the name Daniel James, who is a carpenter at Saint John’s, in Antigua, and also a member of the same congregation; that the Petitioner and the said Daniel James have lived together ever since as man and wife; that about ten months ago the Petitioner arrived in London, with her master and mistress, in the capacity of nurse to their child; that the Petitioner’s master has offered to send her back in his brig to the West Indies, to work in the yard; that the Petitioner expressed her desire to return to the West Indies, but not as a slave, and has entreated her master to sell her, her freedom on account of her services as a nurse to his child, but he has refused, and still does refuse; further stating the particulars of her case; and praying the House to take the same into their consideration and to grant such relief as to them may, under the circumstances appear right. Ordered that the said Petition do lie upon the table.” In the following text, Mary (aka Molly Wood) describes her life as a slave in the Wood household, as excerpted from The History of Mary Prince (author unknown): “Mr. Wood took me with him to Antigua, to the town of St. John’s, where he lived. This was about fifteen years ago. He did not then know whether I was to be sold, but Mrs. Wood found that I could work, and she wanted to buy me. Her husband then wrote to my master to inquire whether I was to be sold? Mr. D____ wrote in reply, ‘that I should not be sold to anyone that would treat me ill.’ It was strange he should say this when he had treated me so ill himself. So I was purchased by Mr. Wood for 300 dollars, *(or £100 Bermuda currency). “My work there was to attend the chambers and nurse the child, and to go down to the pond and wash clothes. But I soon fell ill of the rheumatism, and grew so very lame that I was forced to walk with a stick. I got the Saint Anthony’s fire, also, in my left leg, and became quite cripple. No one cared much to come near me, and I was ill a long long time; for several months I could not lift the limb. I had to lie in a little old out-house, that was swarming with bugs and other vermin, which tormented me greatly; but I had no other place to lie in. I got the rheumatism by catching cold at the pond side, from washing in the fresh water; in the salt water I never got cold. The person who lived in next yard (a Mrs. Greene) could not bear to hear my cries and groans. She was kind, and used to send an old slave woman to help me, who sometimes brought me a little soup. When the doctor found I was so ill, he said I must be put into a bath of hot water. The old slave girl got the bark of some bush that was good for the pains, which she boiled in the hot water, and every night she came and put me into the bath, and did what she could for me: I don’t know what I should have done, or what would have become of me, had it not been for her — My mistress, it is true, did send me a little food; but no one from our family came near me but the cook, who used to shove my food in at the door, and say; ‘Molly, Molly, there’s your dinner.’ My Mistress did not care to take any trouble about me; and if The Lord had not put it into the hearts of the neighbors to be kind to me, I must, I really think, have lain and died. “It was a long time before I got well enough to work in the house. Mrs. Wood, in the meanwhile, hired a mulatto woman to nurse the child; but she was such a fine lady she wanted to be mistress over me. I thought it very hard for a coloured woman to have a rule over me because I was a slave and she was free. Her name was Martha Wilcox; she was a saucy woman, very saucy; and she went and complained of me, without cause, to my mistress, and made her angry with me. Mrs. Wood told me that if I did not mind what I was about, she would get my master to strip me and give me fifty lashes; ‘You have been used to the whip,’ she said, ‘and you shall have it here.’ This was the first time she had threatened to have me flogged; and she gave me the threatening so strong of what she would have done to me, that I thought I should have fallen down at her feet, I was so vexed and hurt by her words. The mulatto woman was rejoiced to have power to keep me down. She was constantly making mischief; there was no living for the slaves — no peace after she came. “I was also sent by Mrs. Wood to be put in the Cage one night, and was next morning flogged by the magistrate’s order, at her desire, and this all for a quarrel I had about a pig with another slave woman. I was flogged on my masked back on this occasion; although I was in no fault after all; for old Justice Dyett, when we came before him, said that I was in the right, and ordered the pig to be given to me. This was about two or three years after I came to Antigua.” In the same book, John A. Wood is quoted in an August 18, 1828 court document as follows: “The paper which Mr. Wood had given her (Molly) before she left his house, was placed by her in Mr. Stephen’s hands. It was expressed in the following terms:– “I have already told Molly, and now give it her in writing, in order that there may be no misunderstanding on her part, that as I brought her from Antigua at her request and entreaty, and that she is consequently now free, she is of course at liberty to take her baggage and go where she pleases. And, in consequence of her late conduct, she must do one of two things — either quit the house, or return to Antigua by the earliest opportunity, as she does not evince a disposition to make herself useful. As she is a stranger in London, I do not wish to turn her out, or would do so, as two female servants are sufficient for my establishment. If after this she does remain, it will be only during her good behavior; but on no condition will I sallow her wages or any other remuneration for her services. /s/ John A. Wood, London, August 18, 1828.”

Ownership Chronology

- 1671: John Wood

- 1750: James Langford – Will 1726

- 1779: Jonas Langford Brooke Baptized 1730. Will 1758. (1777/78 map by cartographer John Luffman.)

- 1820: Peter Langford Brooke d.1829.

- 1829: Peter Langford Brooke Baptized 1793. d. 1840. 280 acres, 190 slaves

- 1851: Thomas Langford Brooke

- 1878: Heirs of Thomas W. Langford Brooke

- 1891: Antonio Joseph Camacho d. 1894

- 1894: A. J. Camacho & Bennett

- 1933: Mrs. Aubrey J. Camacho

- 1938: Millicent Sutherland – The estate contained 280; sold to her for £800

- 1978: Helen (Nellie) Agnes Abbott 18331715& George Scott Sutherland

- 1985: Divided between five members of the Abbott family: Jackson, Helen, Edward, Peter & Philip.